john dyer

John Dyer is a photographer. He has a Masters of Arts degree from the University of Texas where he worked with Russell Lee and Garry Winogrand.

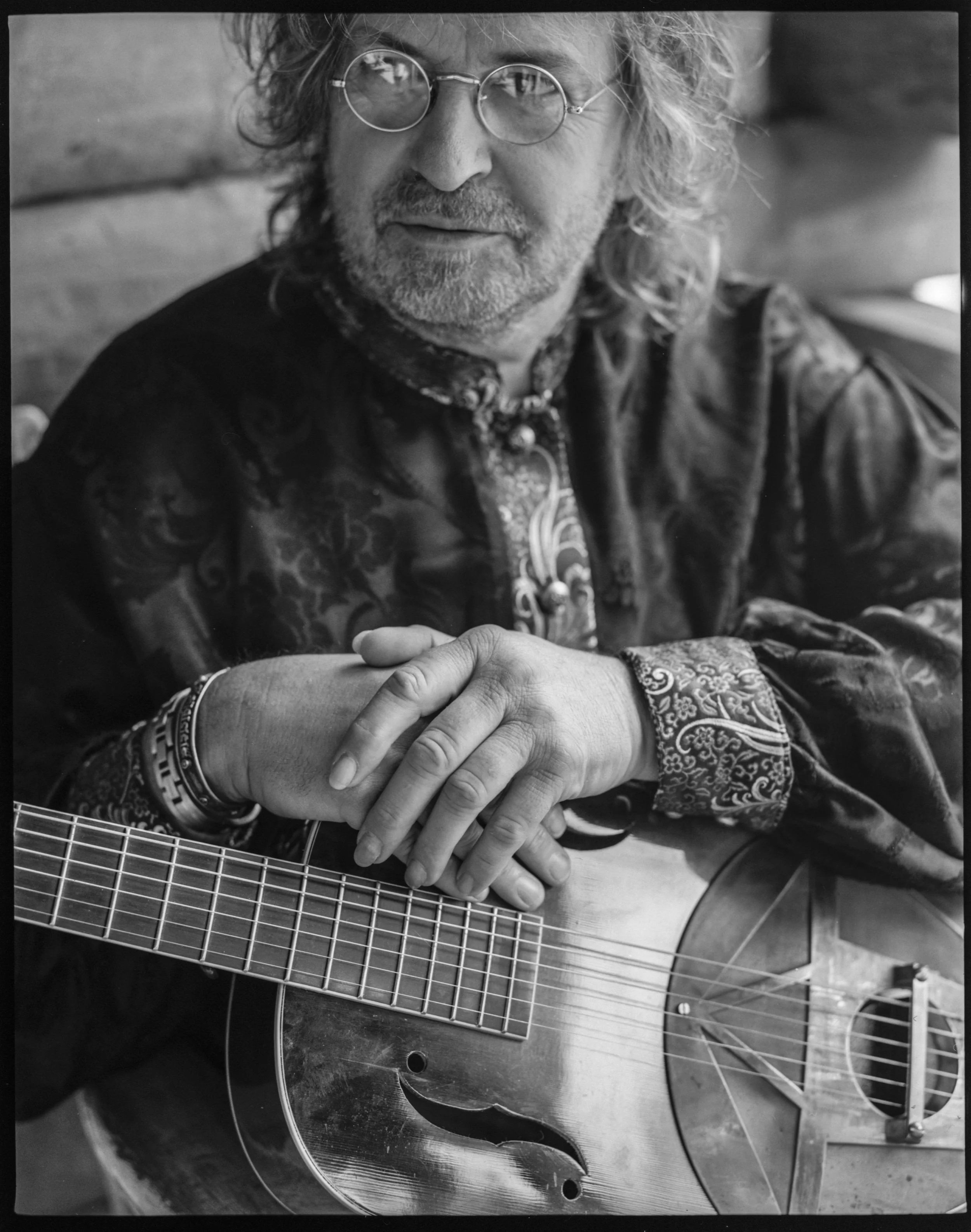

He is the author of Conjunto (University of Texas Press, October, 2005), El Vaquero Real, The Original American Cowboy (Bright Sky Press, September, 2007) and San Antonio Hidden Treasures (Private Commission, 2011). Edge of Texas was shot in 2019 and is yet to be published.

John has exhibited his photographs at a wide variety of museums and galleries and is represented by Heidi Vaughan Fine Art in Houston, Texas. John’s portrait of Selena was exhibited in Icons of Style, in 2020, at the Fine Arts Museum Houston and is part of their permanent collection. In 2019, the National Portrait Gallery acquired one of his Selena portraits for their permanent collection. John’s exhibition, Selena Forever/Siempre Selena, originated at the McNay Museum of Art in San Antonio, and has since travelled to Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art and is currently at the El Paso Museum of Art.

John lives with his wife, the painter Diane Mazur, in San Antonio, Texas.

About The Selena Series

She drove up by herself in her little red hatchback and parked in front of my studio. I had gotten a call from Mas Magazine, a magazine devoted to Latino culture and lifestyle. They wanted a cover and main spread profiling this young Texas singer who was starting to make a name for herself in the world of Tejano music. I had heard of Selena but I didn’t know very much about her and certainly had no idea of what was to come.

I spent the day before the shoot setting up several backdrops in the studio so I could photograph her in a variety of situations and costumes. I knew I had her for the full day and wanted to take advantage of our time together.

She jumped out of her car with a big smile. A naturally beautiful young Latina with jet-black hair, flawless skin, and a perfect figure. She opened the hatchback. It was crammed full of her preforming costumes, many hand made, all of her own design.

We shot roll after roll of transparency film (this was before digital photography). For the cover, we shot in front of a gray background. Then we moved in front of a red curtain above a black and white checked floor. We ended outside the studio against a white seamless in the warm afternoon light. Selena’s quick smile, infectious laugh, and unending energy made her a pleasure to work with. This was in 1992.

In early 1995, Texas Monthly called and wanted to do a spread on Selena. By now, she had achieved incredible fame and transcended the boundaries of the Texas music scene. We met at the Majestic Theater in San Antonio, a favorite place of mine. She had just finished two exhausting days of shooting TV commercials for a corporate sponsor. She was tired. I had brought a beautiful hand-made jacket for her to wear. I posed her in the alcove on the mezzanine of the theater where the light is particularly nice. She was subdued and pensive. A far cry from the ebullient, excited young singer I’d photographed 3 years earlier. Later I thought her mood might have been an eerie harbinger of what was to come.

Between when I photographed her at the Majestic and the Texas Monthly article coming out, she was killed. The art director, my old friend DJ Stout, used one of the more somber shots I had done for his cover chronicling her death. He sent me a hand written note not too long after the issue appeared saying the cover with my photograph of Selena was one of the strongest he’d ever done. It’s a cover I would rather not have had.

Selena’s senseless, tragic death on March 31, 1995, shocked millions and continues to sadden to this day. She was 23.

About The north american indian days

A yearly celebration of Indian dancing that takes place in Browning, Montana, the headquarters of the Blackfeet Nation.

“The North American Indian Days is a yearly celebration of Indian dancing that takes place in Browning, Montana, the headquarters of the Blackfeet Nation. It draws dancers from all over the western United States and Canada. It has been going on for many years, except for the Covid pandemic. The celebration was cancelled in 2020 and 2021. I had been to the NAID twice before, once in 1987 and again in 2000. Both times I photographed the dancers using film. In the summer of 2020, I went again to photograph, this time using a digital camera. The celebration was billed as the “Recovery”. It was quite crowded. The tent where the dancing took place was too small and dimly lit and was not the best place to show off the incredibly beautiful, elaborate regalia (never call what the dancers wear a costume!). Nevertheless, the dancing took place and, as always, was accompanied by the drumming and singing. My idea was to invite some of the dancers to allow me to photograph them. Fortunately, near the tent was a ring of tepees that gave me a somewhat neutral background to take my portraits. Otherwise, the background was a jumble of campers, cars, trucks, etc. I had a small notebook with me and, as carefully as I could, took down the names of the dancers, their tribe affiliation, where they lived and e-mail addresses. It’s my habit to always send the best shot of my subjects to them as a thank you. I would also respectfully ask each if they would tell me their Indian name. Indians always have an “English” name and, many an “Indian” name that is given to them in a sacred ceremony. I had been cautioned by a Blackfeet elder to tread lightly when asking for an Indian name. “It’s kind of personal,” she had said. Some told me their Indian names. Some didn’t. This folio represents what I think are the best photographs.”

Selected Exhibitions:

2025- Witliff Collection acquisition of musician and “Conjuncto” photographs

2025- The King Ranch Museum acquisition of Los Kineños

2024- El Paso Museum of Art acquisition of Selena portrait

2024- “Selena Forever/Siempre Selena,” El Paso Museum of Art

2023- “Selena Forevere/Siempre Selena,” Eagle Pass Cultural Art Center

2021- “Selena Forever/Siempre Selena,” Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art (exhibition of Selena photographs to run through January 2022)

2020- National Portrait Gallery acquisition of Selena photograph

2020- “Selena Forever/Siempre Selena,” McNay Art Museum

2020- Museum acquisition of two photographs from “El Vaquero Real, the Original American Cowboy,” Briscoe Western Art Museum

2019- “Icons of Style,” Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

2011- “Artists on Art” series, McNay Art Museum

2009- Photographs from “El Vaquero Real, the Original American Cowboy,” Greasewood Gallery, Marfa, Texas

2008- “The Sounds I See: Photographs of Musicians,” Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

2008- Photographs (and paintings by Lionel Sosa) from “El Vaquero Real, The Original American Cowboy,” Kenedy Ranch Museum, Sarita, Texas

2008- Photographs (and paintings by Lionel Sosa) from “El Vaquero Real, The Original American Cowboy,” Webb County Historical Museum, Laredo, Texas

2007- Photographs (and paintings by Lionel Sosa) from “El Vaquero Real, The Original American Cowboy,” Witte Museum

2007- “Conjunto Photographs,” Museo Alameda de San Antonio (Smithsonian Institution)

2006- “Conjunto Photographs,” Oswald Gallery, Austin, Texas

2005- “Conjunto Photographs,” International Museum of Art and Science, McAllen, Texas

2005- “Conjunto Photographs,” Narciso Martinez Cultural Art Center, San Benito, Texas